If you look from the point of view of cultivating or acting from an impartial compassion, a compassion that goes out to everybody equally, you can view abusive situations within Buddhist communities from four different angles:

- What do those abused need?

- What does the perpetrator need?

- What does the organisation / institution need?

- What does the community need?

If you choose a long term perspective – considering long term benefit and long term harm – then, in general, what I understand so far is:

The bodhisattva does not follow many Dharmas. The bodhisattva holds one Dharma well and realizes it well. The whole Buddhadharma will be in the hand of that person. What is that Dharma? It is great compassion. – Chenrezig Sutra Well-Condensed Dharma

1) The abused need to be heard and taken seriously. Then help should be offered according to her/his needs and wishes – without pressuring or manipulating her/him to either stay silent or to go public. Also the perpetrator and the leadership of the organisation should take responsibility, acknowledge the harm their own actions (or inactions) have caused and honestly excuse. Further steps according to the needs and situation should be taken, like offering financial help for therapy or financial compensations to balance the harmful impact abuse has had on the person’s life – for instance, trauma that prevents a person from being able to have a secure income / job or limits her/his ability to work for more than a few hours or that requires a longer reconvalescence treatment.

In the long term, the abused need support for her/his process of healing. In an interview for this blog psychotherapist Kata outlined three possible steps:

- to see and to accept that abuse happened,

- to understand how the abuse happened and the role of everybody involved,

- to process on the path by taking responsibility for what one can control and to find solutions to move on.

When an accused abuser is exonerated, he doesn’t take it as a chance to reflect on his conscience and reform his acts. He is being told by the patriarchy that he is invulnerable. – Bhante Sujato

2) The perpetrator needs to be given clear boundaries. He or she must be faced with / made aware of the wrong doing. He/she should be offered psychological or qualified help. He or she needs to experience a consequence for the harmful action that is neither too strong nor too weak. The perpetrator, who is also a victim of the kleśas (mind poisons such as attachment, anger or confusion etc and an inability to regulate these), should get a chance to change through better understanding and finally by weakening or overcoming the harmful patterns that led to the abusive action(s). He or she should be supported to be successful in that. Moreover, the perpetrator should not be put in an environment or situation (such as a teaching position) that might trigger his/her inner patterns so much that he or she loses control again and repeats the abusive action. Of course, criminal acts should be reported to the police. Being sentenced to prison might be just the right consequence for the perpetrator. To stop the perpetrator, to set boundaries, to issue consequences for misdeeds and offer help to overcome the harmful patterns that gave rise to abusive actions can be in itself a deeply compassionate action. Nobody is served – not the perpetrator [because harmful actions harm him/herself], not the victims, not the community and not the society – if a perpetrator is not prevented from harming others or not provided a context in which he or she can learn from and to let go the harmful behaviour.

3) Leadership of institutions or organisations where abuse happens likely will feel threatened that their organisation is going to be harmed when the abuse comes to light. This likely will result in fears that the organisation will face a (possibly huge) loss of reputation undermining their very mission and good work. So, it is natural to intuitively respond to allegations of abuse by repressing public access to it – or to keep it in the shadows or to put more darkness on it.

It is not healthy, of course, for disciples to deny serious ethical flaws in their guru, if they are in fact true, or his or her involvement in Buddhist power-politics, if this is the case. To do so would be a total loss of discriminating awareness. – 14th Dalai Lama

However, from a long term perspective, to cover up the abuse, to silence, threaten, manipulate / gaslight, ostracise or slander the victims or whistle blowers sends the wrong signal to the perpetrator (and also to people with a potential to become perpetrators too) – implying that the wrong actions are accepted, that misbehaviour or abuse is no real ethical problem for which anyone needs to be concerned or is held accountable. It sends the message to people within the institution and those who have been harmed that the leadership doesn’t care about their members’ well being but only the organisation’s reputation. As a result, such an approach in dealing with accusations of spiritual, emotional, financial or sexual abuse within an organisation, gives space for further abuse and unethical conduct to continue and increase. More cases of harm increase the possibility that more will sooner or later be reported and become public. Then, when these enabled, tolerated, destructive and harmful actions are publicized, the public will be shocked. And what happens then? The reputation of the organisation will be harmed far more than if the leaders had been transparent from the start. (Though, from a humanitarian perspective, worse is that more harm to human beings has been enabled and contributed to by the unskillfulness of the leadership – but this seems often not to be the main concern of the leadership which reversely will reflect bad on the leadership.) So, even when leaders of organisations care more about their reputation than the well being of their members, it is wiser to address misconduct in the first place when it is first reported, in a professional and serious (see point 1) and 2)) manner and to be transparent about that, to speak and act truthfully and compassionately.

Buddhist teachers who abuse sex, power, money, alcohol, or drugs, and who, when faced with legitimate complaints from their own students, do not correct their behavior, should be criticized openly and by name. This may embarrass them and cause them to regret and stop their abusive behavior. Exposing the negative allows space for the positive side to increase. – 14th Dalai Lama

4) The well being of the community is served on the one hand if points 1) to 3) are acted upon accordingly.

Additionally, a fair, open, transparent communication within the organisation is a factor for healing. Compassion that gives space for listening to or holding people who are angry, upset, disillusioned, sad, at pain, in fear, disparate should be cultivated or allowed to arise. Speaking openly together on how the situation can be dealt with in a healing manner, in a dharmic manner, and in an impartial compassionate manner – maybe guided by a professional mediator and procedure – might contribute to healing. Also to invite experts who can educate the community regarding what factors lead to such situations, what measures must be taken to prevent such situations in the future might be a good means to contribute to healing. Deeply honest self-reflections – or maybe even open discussions (without seeking to blame anybody and with mutual respect and love) – about members’ own bystander modes, their own inactions, their own denials, their participation in silencing, reframing abuse as beneficial for the victims, their own contributions in ostracising, gaslighting, slandering victims are in, my opinion, of crucial importance. Why? Because only if one understands the complex dependent arising that gave space / enabled / caused the abuse and individuals’ own role in that dependent arising their own ignorance, that led to the abuse as its cause, can be seen, reduced or overcome by insight into the many causes and conditions. Once members’ own parts or contributions within this complex dependent arising are seen, then, and only then, can members take responsibility for their own actions that formed a part of the frame in which abuse occurred. Taking responsibility for their own actions – just as the perpetrator – and then undertaking actions which aim to heal or repair that damage – like honest apologies, confession, feeling or expressing regret, inner or verbal promises not to do that again are also good factors for healing and purifying these actions, aren’t they? Self-compassion and self-forgivingness after these insights and reparation means is also needed and contribute to healing. Those who are self-compassionate and self-forgiving, who understand themselves, find it far easier to understand others, to feel compassion for others and to forgive them. In that way the destructive cycle of blaming and condemning others comes to a halt.

In the context of critical introspection within the community, it is important to evaluate the doctrines spread and taught in the group (such as instructions that the guru and his or her actions must be seen at all times as enlightened or holy, that the guru is always right, that the student – if not in line with the guru – is always wrong) must be questioned or re-evaluated. Some doctrines might have been abused to manipulate, gaslight, and control students and are now spoilt or poisoned because of egoistic or deluded motivations. Continuing to teach these in unreflected, non-debunked or non-differentiated ways can trigger students and harm them. … Actually, there is a lot to do, these are just some quick thoughts based on my own experiences and observations. However, a restorative ritual can only come after this work has been done.

So in summary, an honest, truthful, transparent, impartial compassionate and wise approach will increase trust and faith.

The Buddha understood that an institution is served by truth and accountability. – Bhante Sujato

A dishonest, deceptive, manipulative, partially-compassionate (caring more about the perpetrator or the organization than the victim) approach, an approach in which the leadership and / or the perpetrator don’t take responsibility and openly excuse and learn openly from what has happened and acknowledge their own faults will highly likely cause distrust, rumours, lies and will end in quarrel and deep rifts or splits in the community / sangha – it will destroy the social cohesion and split the community.

Lying is disruptive to social cohesion. People can live together in society only in an atmosphere of mutual trust, where they have reason to believe that others will speak the truth; by destroying the grounds for trust and inducing mass suspicion, widespread lying becomes the harbinger signalling the fall from social solidarity to chaos. But lying has other consequences of a deeply personal nature at least equally disastrous. By their very nature lies tend to proliferate. Lying once and finding our word suspect, we feel compelled to lie again to defend our credibility, to paint a consistent picture of events. So the process repeats itself: the lies stretch, multiply, and connect until they lock us into a cage of falsehoods from which it is difficult to escape. The lie is thus a miniature paradigm for the whole process of subjective illusion. In each case the self-assured creator, sucked in by his own deceptions, eventually winds up their victim.Bhikkhu Bodhi

Written by Tenpel. Edited by Joanne Clark.

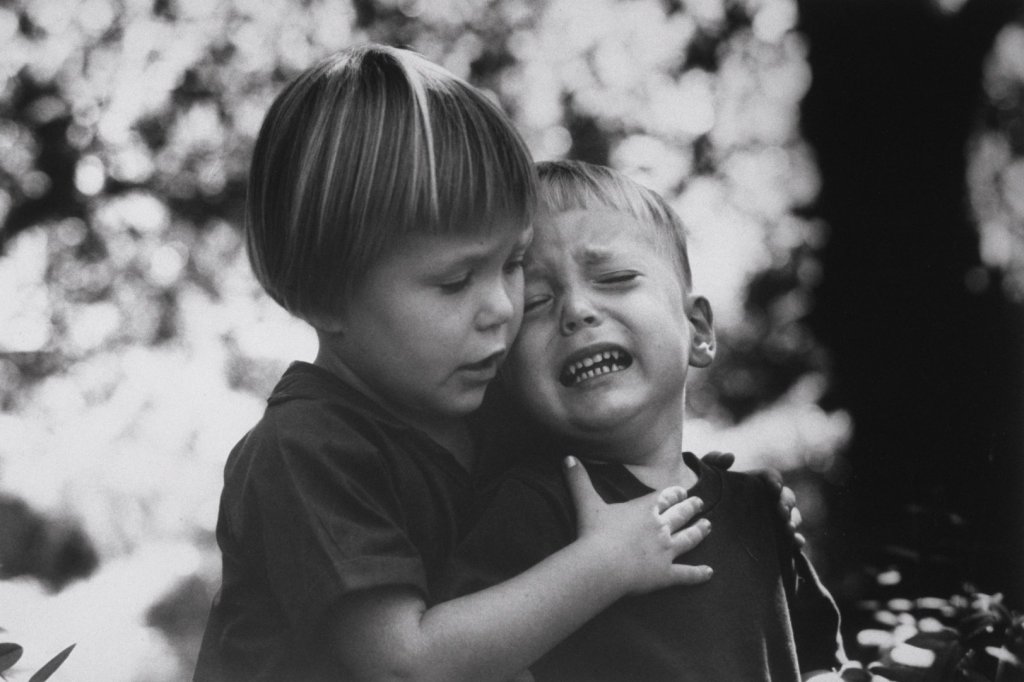

© Image by Carroll Seghers (SCPhotos / Alamy Stock Foto)

Reposted in Dutch “Wangedrag binnen boeddhisme – een oproep tot onpartijdig mededogen”

See also

- What is DARVO? – Jennifer J. Freyd, PhD

- Gaslighting and consent – Meg-John Barker

- The Dalai Lama on Abuse by Buddhist Teachers or Gurus October 10, 2017

- The Devil You Know by Dr Gwen Adshead and Eileen Horne review – hope for the worst of humanity – The Guardian

- Not to extend our natural compassion and kindness to others makes us a ‘world killer’ – says the 17th Karmapa June 8, 2020

- On the Road to Healing from Abuse in Buddhism – An Interview with Kata November 18, 2019

- Clergy Sexual Abuse & Buddhist Ways of Dealing With Abuse (2018/03/15)

- El criminal, la víctima y el monje – Interview with Tenzin Peljor (English with Spanish subtitles, Jan. 2022)

Related Articles

- The Buddha Would Have Believed You – Bhante Sujato

- Differing Perspectives, Compassion in the Buddhist and Christian Traditions – Alexander Norman

- Buddha about Intimate Friends – The Buddha in the Mitra-vargha (Tibetan Dhammapada)

- Ethics in the Teacher-Student Relationship: The Responsibilities of Teachers and Students by H.H. the XIV. Dalai Lama

- Questioning the Advice of the Guru by H.H. the XIV. Dalai Lama

- Treat Everyone as the Buddha – Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche

- Dealing with Abusive Behavior by Spiritual Teachers – Alexander Berzin

- Relating to the Guru by Jetsünma Tenzin Palmo

- Devotion with Discernment – A question of personal responsibility by Rob Preece

- Breaking the Silence on Sexual Misconduct – Lama Willa B. Miller (Lion’s Roar)

- Advice for Women in a Secret Sexual Relationship with Their Buddhist Teacher – Lama Willa B. Miller (Lion’s Roar)

- The Guru Question: The Crisis of Western Buddhism and the Global Future of the Nalanda Tradition – Joseph Loizzo

- What Went Wrong: An interview with Tibetan psychologist Lobsang Rapgay about student-teacher relationships that turn abusive – Tricycle Winter 2017